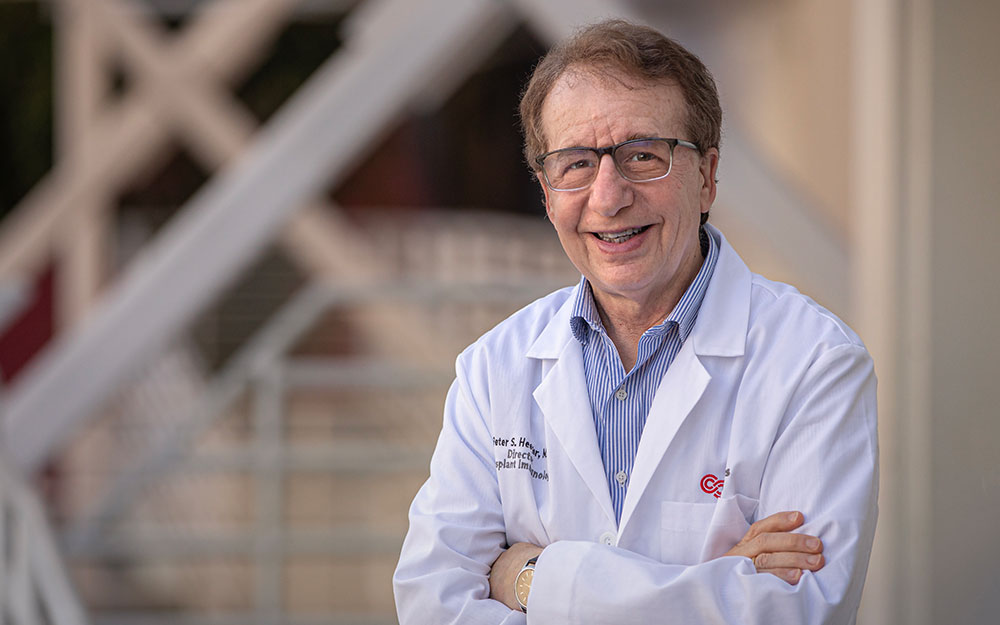

Meet Transplant Surgery Trailblazer Irene Kim, MD

Date

November 10, 2021

Credits

Date

November 10, 2021

Credits

Medical providers featured in this article

In Brief

{{cta-block}}

Quick on her feet, Irene Kim, MD, does not let a single moment slip away from her. The co-director of Cedars-Sinai’s Comprehensive Transplant Center, mom of two and avid runner has learned to expect the unexpected—and pivot accordingly. Set to take the reins as center director this December, she opens up about what drives her, the gift of life and what’s ahead for organ transplantation.

Q. What drew you to transplant surgery?

During my residency at Tufts Medical Center, three transplant surgeons, to me, embodied humanism, compassion and surgical prowess. They inspired me and I decided I wanted to pursue this career. People really tried to dissuade me. They said it was a difficult field with no protected hours and that I would have no life. But I just couldn’t break from this notion of what being a surgeon meant to me and how you are able to actually save someone’s life through organ transplant. There’s something about that feeling of one family making this huge sacrifice to save another person that is so special. The field I chose is hard, but I have no regrets. I absolutely love what I do. I love my patients.

Q. What are you most proud of?

I am most proud of the contribution I’ve made to creating a cohesive transplant team that really cares for our patients and for one another. I’m proud of my leadership in helping to create that team, whether it’s the physicians I’ve personally recruited or the example I hope I provide. I’m also proud of the research I’ve done that can be applied directly to care, especially my investigation into the effects of blocking inflammatory molecules that trigger an immune response. This allowed us to suppress the production of antibodies that would attack the new organ. It enables transplantation in people with strong antibody responses and increases graft lifespan after transplantation.

Q. How do you find balance across all the different aspects of your life?

My parents retired when our daughter turned 1. They moved into our house in Los Angeles and they help us out a lot with our family. It is a rare situation. It’s partly cultural but also just the goodness of my parents’ hearts. There’s a definite surprise element in transplantation, because it’s based on generosity and the incredible gift of donors. Transplants often happen at nighttime, on the weekends and at random hours of the day. And they’re long operations; a liver transplant can take six, eight, sometimes 12 hours. My family, in turn, has to be flexible. They know that when I’m on call they’re on call, and they fill in the void when I’m not there. My kids are very resilient—they understand that and know when Mommy has to be away.

Q. As you take the helm, what is your vision for the future of the Comprehensive Transplant Center?

We are going to continue to expand as a transplant program. We are already leaders in many aspects of transplantation. I want to see Cedars-Sinai get out ahead in relatively young transplant fields such as hand and limb transplants. And as we develop more research around barriers in transplantation, I hope we will be able to overcome them—for example, for patients who have immunologic obstacles preventing them from being transplant candidates.

I also want to focus on equity and inclusion. Many marginalized communities are not given access to transplantation, whether it be due to language or socioeconomic or immigration status. I see us participating in outreach efforts for patients who might need a liver or kidney transplant but have not been introduced to that as a concept.

Q. Where do you think transplant medicine is headed?

There hasn’t been a newer generation medication to prevent organ rejection in over 20 years. The goal is minimizing the quantity of medications that a transplant patient has to take, then cutting down on adverse side effects. The holy grail is reaching a state where patients may not need immunotherapy at all. The other main challenge is the lack of organs. Many patients die waiting for an organ transplant. An old mentor used to tell me, “If they grew on trees, we’d be transplanting left and right.” So why can’t we get them to grow on trees? Why can’t we create a bioartificial organ?

Family Affair

Kim met her husband in medical training. After a decade of marriage and a cross-country move, their daughter, 6, and son, 3, were born at Cedars-Sinai. The couple both have demanding careers, one in medicine and the other in a technology strategy firm, but they always try to eat dinner together as a family. "My Korean heritage is important to me, so our family meals are usually influenced by Korean culture," Kim says.

Setting an Example

Surgical fields have lagged behind in diversity, Kim says. She was the first woman to join Cedars-Sinai's transplant surgery group.

"I hope that I serve as an example that you can be a woman and a person of color and be a very welcome, necessary part of a surgical team."

Racing Ahead

With an erratic surgery schedule, she squeezes in a run whenever she has a spare hour and a half. Whether with friends or on her own on trails, running is her main release.