Discoveries

Cedars-Sinai Experts Discuss the Mysteries of Memory

Sep 11, 2024 Sarah Spivack LaRosa

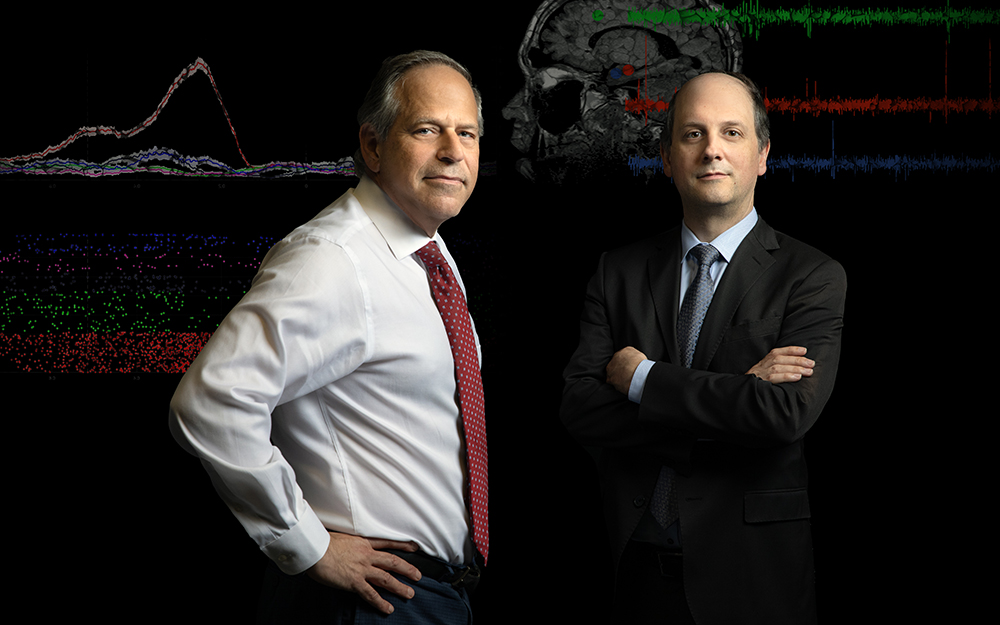

Ueli Rutishauser, PhD, and Adam Mamelak, MD, study the neural mechanisms of learning, memory and decision-making. In one recent study, published in Nature, they identified for the first time the way specific neurons coordinate focus in working memory. Another study, also published in Nature, is the first to demonstrate the dual neurological processes that allow humans to learn rapidly: ignoring irrelevant details and making educated guesses.

In a broad discussion with Discoveries, edited for clarity, Rutishauser, director of the Center for Neural Science and Medicine and the Board of Governors Chair in Neurosciences, and Mamelak, director of the Functional Neurosurgery Program, discuss how their work informs their perspectives on the mind and how their study of the human brain exemplifies Cedars-Sinai’s mission to simultaneously gain scientific insight and improve the lives of patients.

Humans are uniquely human, and while much valuable research is performed in animals and cell cultures, to answer fundamentally human questions, we need to probe human brains and ask fundamental questions that have a real connection to the human mind."

-Dr. Adam Mamelak

Your research uncovers correlations between mental states and neural states. Is there a difference between the brain and the mind?

Adam Mamelak: It’s not possible to make a definitive statement, given our immature knowledge base today. The brain is the structure that physically generates memories and senses and perceives the world based on underlying mechanisms. Does that imply some underlying deeper process? It doesn’t exclude that possibility, at least in my opinion. But the working assumption in neuroscience is that if you understand brain networks and mechanisms, you will, in turn, understand the mind.

Ueli Rutishauser: Ultimately, the brain creates the mind—or rather, the body creates the mind. We are starting to understand more about the mechanisms of memory, how we make decisions, and different moods and aspects of personality. We are at the very beginning, but it’s clear that one should not regard the brain as an isolated entity; there are interactions with so many different parts of the body. Those are also part of your mind.

Your research shows that we segment our memories, despite experiences being continuous. Is memory accurate?

UR: Studies show that many aspects of memories that we believe are accurate are basically made up. You might really believe, for example, that you can describe your childhood room in great detail. But if one really checks on the details, the memory is inaccurate. We fill in the blanks. It’s constructed, to a shocking extent, and very unreliable.

AM: Ueli has pioneered an idea with a very simple task that he’s been testing for years: First, he shows a person 50 pictures one second apart. Then he returns 30 minutes later and presents 100 pictures—half new and half from the first set—and asks, “Have you seen this before?” People tend to do this very well. But they’ll sometimes say, “I've never seen that picture before,” when they actually have, indicating there is a difference between what you remember and what is correct. This is a well-known observation in eyewitness memory, as well.

You have studied novelty and memory processing. What are the selection criteria for creating a long-term memory?

UR: There are a variety of criteria. An important one that we have studied is an event’s salience or novelty when you experience something for the first time.

AM: There’s almost surely an emotional component to it. In post-traumatic stress disorder, the emotional salience is a very dangerous situation associated with the memory. The coupling to the emotional content may modify the significance of the event.

Since so much is novel to children, do they process memory differently?

AM: When you’re young, you just have much less experience. Maybe everything is more unique for kids, and maybe that’s why there’s more capacity to remember individual things. As we get older, those networks get saturated with more and more common situations. Things look more similar, and it’s harder to distinctly, episodically separate them out. That’s a largely theoretical idea, but one that matches what we observe with memory development in children.

UR: One of the big mysteries in memory is childhood amnesia: We remember nothing about our early childhood. Those early memories don’t transfer into adulthood. One theory says that this is deliberate. Another theory is that our scaffold of knowledge isn’t well developed in childhood, so these memories cannot be referenced anymore. And there are other theories that say that the concept of episodic memory hasn't emerged yet. But childhood amnesia is not fundamentally understood.

Why do adults "actively forget"?

UR: It’s related to learning. To learn is not to remember everything you experience, but to abstract away something more general that you can apply to new situations. So, learning has a lot to do with forgetting—choosing not to remember irrelevant details.

What makes your work significant?

AM: Humans are uniquely human, and while much valuable research is performed in animals and cell cultures, to answer fundamentally human questions, we need to probe human brains and ask fundamental questions that have a real connection to the human mind. Yes, this work can lead to treatments and cures, but there’s also an intrinsic interest in exploring the unknown. This type of work really does both: It may potentially lead to novel ways to approach diseases and disorders. But it can also lead to a greater understanding of who we are and what we are.