Latino Patients Have Higher Rate of Gastric Cancer Diagnosis, Survival

Date

January 24, 2022

Date

January 24, 2022

Credits

Medical providers featured in this article

In Brief

{{cta-block}}

The incidence of gastric cancer in the United States has slowly declined over the last decade, but it remains a leading cause of cancer-related death globally. In Los Angeles County, Cedars-Sinai physicians began to notice that the prevalence of the disease seemed to be outpacing the rest of the country.

"We know gastric cancer is occurring in younger and younger patients. We can intervene in their cancer journey earlier and help them return to health and their families sooner."

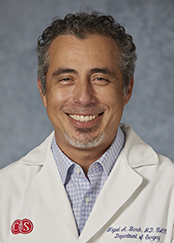

"We are seeing an incidence around 10 to 12 per 100,000 people in Los Angeles County," says Miguel Burch, MD, chief of Minimally Invasive and GI Surgery. "That’s about double the rate throughout the rest of the country, which could be because of the mix of ethnicities here."

In particular, the team noticed a lot of Latino patients in their 30s and 40s presenting with very aggressive cancer despite being otherwise healthy. This was especially perplexing since gastric cancer tends to impact an older population.

The team decided to dig deeper and look at the demographics, socioeconomic factors, and treatment and survival experiences of Latino patients.

Increased incidence and socioeconomic barriers

To help determine the scope of the pattern of increased incidence, Burch and his team consulted the National Cancer Database and identified more than 90,000 patients diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma between 2004 and 2015. Of that 90,000, more than 12,000 were identified as Latino with diagnoses across all stages.

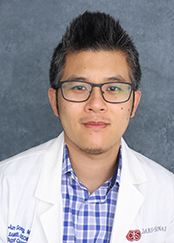

"The National Cancer Database sources data from more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the Commission on Cancer," says Jun Gong, MD, a medical oncologist in the Gastrointestinal Disease Research Group and one of the study’s coauthors. "What we were able to compile is probably one of the largest cohorts of Latino patients with gastric cancer ever documented."

Researchers saw a 40% increase in the incidence of gastric cancer in Latino patients upon evaluation of the data. Comparatively, data reflecting the diagnoses of non-Latino white patients—those from European, Middle Eastern or North African regions—suggested only a 4% increase.

"Furthermore, we found that the Latino patients diagnosed with gastric cancer were more likely to be younger, more likely to be female and were technically healthier with fewer medical comorbidities," says Gong.

Compared to other populations, Latino patients presented with more aggressive features of the disease clinically or pathologically and tended to come from areas of lower income and education status. However, they were more likely than comparators to have access to care within 10 miles of their home and more likely to receive treatment at a high-volume academic medical center.

"The data also showed that Latino patients were more likely to have positive margins after a curative intent surgery, which is a poor prognostic indicator as it means the entire tumor is not removed," says Gong. "These patients were also less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, which is often the standard of care, potentially due to some of the socioeconomic barriers mentioned."

Improved survival despite disparities

Despite the identified socioeconomic barriers and the disparities in surgical outcomes, Latino patients with gastric cancer had improved survival rates when compared to other populations.

"We wanted to evaluate how much impact being Latino specifically had on survival, even correcting for all other factors" says Burch. "So, we used a propensity-matching system to compare the data of statistically identical non-Latino and Latino patients. We found that being Latino was an independent predictor of survival, was more important in predicting survival than even receiving chemotherapy and as important as receiving treatment in a high-volume center or having appropriate lymph node dissection."

There is more to do to investigate the impact of the identified disparities and further improve outcomes in these populations where gastric cancer is on the rise.

"The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has recommended that endoscopic screening should be considered in patients from high-risk regions," says Burch. "But, given the improved survival seen specifically in Latinos even with advanced disease, it raises the question if Latino patients should be screened early and aggressively."

Gong echoes that sentiment, hoping these findings will motivate the field of medicine to continue conducting research and instituting new policies that can positively impact guidelines for screening, diagnoses and treatment.

The next steps

The research team hopes to continue this work with more epidemiological research to better understand the Latino patient population and the best ways to address the obvious disparities. Ultimately, this could take the form of new tests that can assist in screening and diagnosis.

"From a translational standpoint, we can find out more about the biology of the tumors in this patient population," says Gong. "That means investigating the molecular mechanisms of why this paradoxical finding of improved outcomes occurs."

There are also steps that can be taken now.

"In the meantime, we have a real opportunity to help the communities we serve," says Burch. "We know gastric cancer is occurring in younger and younger patients. We can intervene in their cancer journey earlier and help them return to health and their families sooner."