Cedars-Sinai Blog

Hormonal Birth Control Might Reduce Female Athletes’ ACL Tears

Mar 04, 2025 Christian Bordal

Female athletes are two to eight times more likely to tear their anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) than their male counterparts performing the same sport at the same level. They are also at greater risk for other ligament and tendon injuries, such as ankle sprains.

One factor that may contribute to this difference is hormones. So, could hormonal birth control such as the pill—which stops the release of hormones such as estrogen and progesterone—help reduce the risk of injuries for female athletes?

A recent study at Cedars-Sinai, sponsored by its Center for Research in Women’s Health and Sex Differences (CREWHS), went in search of an answer to that question.

What Is an ACL, What Does It Do and Why Are Injuries on the Increase?

In 1972, when Title IX was passed—the law that prohibited sex-based discrimination in schools—fewer than 300,000 women participated in high school sports. Fifty years later, the number is closer to 3.5 million.

Sports participation has been shown to improve mental and physical health, academic performance, and self-confidence. But with so many more females playing competitively, and their greater risk for ACL tears and other joint injuries, we’re seeing a lot more of these injuries in young athletes, said Natasha Trentacosta, MD, a Cedars-Sinai orthopedic surgeon who specializes in pediatric and adult sports medicine.

Natasha E. Trentacosta, MD

“The number of ACL tears for males and females are similar until about age 14, and then all of a sudden there’s a spike for females that’s way higher than for males,” she noted.

The ACL connects your thigh bone to your shin bone, and it prevents the shin bone from coming too far forward in an activity such as skiing. But its more important function is the rotational stability it provides during sudden sideways moves in sports such as soccer, basketball and volleyball.

“When an ACL tears, the thigh and shin bones can continue to twist in opposite directions, and the knee can buckle and collapse underneath you,” explained Trentacosta, the principal investigator in the Cedars-Sinai study. “Aside from being painful, that can also damage other structures in the knee, like the cartilage.”

How Might Hormones Be Involved?

Women’s bodies adapt to pregnancy by becoming more flexible.

“As someone who happens to be pregnant right now, I can confirm this firsthand,” laughed Cedars-Sinai surgical gynecologist Natasha Schimmoeller, MD, another researcher on the study.

A hormone appropriately named relaxin is at least partially responsible for this change. Women have receptors for this hormone on their ligaments, and men do not. The hormone breaks down ligaments’ collagen, causing joints to become looser. It’s a positive adaptation, but it also increases pregnant women’s risk of joint injury, particularly after falls.

Relaxin is not only released during pregnancy, however. In girls, teens and women who are not pregnant, relaxin levels increase in the second half of each menstrual cycle, triggered by ovulation.

“Hormonal birth control methods such as the pill inhibit ovulation, so they keep relaxin levels low,” explained Schimmoeller. “The theory we’re testing in our study is that, over time, their use will reduce injury risk in female athletes.”

Natasha R. Schimmoeller, MD

The Results: How Does Birth Control Affect Ligaments?

The study looked at 72 high-level collegiate athletes, 32 of whom used hormonal birth control. Researchers collected blood to measure hormone levels, and they tested the looseness of the athletes’ ligaments.

The Beighton test measures upper and lower body flexibility and returns a score based on the subject’s ability to, for example, touch their pinky finger to their forearm or reach the ground with flat hands or fingertips while keeping their legs straight.

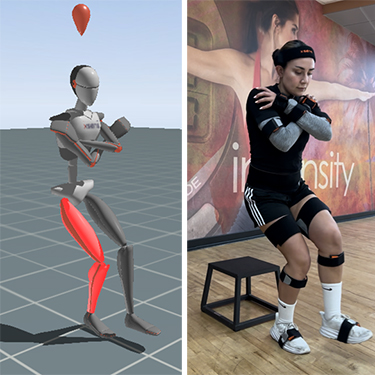

"We also had them jump off a block on one leg," said Cedars-Sinai researcher Melodie Metzger, the study author.

The researchers measured how much the athletes’ hips flexed and how much sideways movement there was in their knees when they landed. More sideways joint movement indicates greater risk of ACL injury.

"To be honest, I didn’t think we’d see anything, because is birth control really going to change how you move?" asked Metzger. “But the results demonstrate that it does. We found different hip and knee movement in women who were in the second half of their menstrual cycle and were not on hormonal birth control compared to those who were. So, these women who were on birth control were protected because they landed with their hips straighter and their knees more parallel: They didn’t knock their knees together as much.”

The researchers also tabulated all injuries the athletes experienced over the course of the study, including ankle sprains and strains, meniscal tears and knee hyperextensions. They found athletes with lower relaxin levels due to their use of hormonal birth control had fewer of these injuries.

“Hormonal birth control methods such as the pill inhibit ovulation, so they keep relaxin levels low.”

Should All Young Female Athletes Be on the Pill?

“We’re just providing the information that there may be this added protective benefit to hormonal birth control,” said Schimmoeller. “That’s in addition to other health benefits of hormonal birth control—such as decreasing the volume of women’s periods, decreasing menstrual pain and perimenstrual mood disorders, and decreasing ovarian and uterine cancer risk. And it’s very safe and covered by insurance.”

Trentacosta is quick to point out that hormones are not the only contributor to the increased risk of ACL tears for female athletes.

“Women’s pelvises are wider, so we tend to have more of a knock-kneedness,” she said. “Men have relatively stronger hamstrings, whereas the quadriceps tend to be more dominant in women. And that’s actually less favorable for the ACL, because it puts more stress on it.”

Trentacosta says female athletes can reduce their risk of ACL injuries by engaging in training programs that strengthen stabilizing muscles, such as the hamstrings and gluteals.

The three researchers still have many questions about the effect of hormonal birth control on athletes and are planning further studies with a larger cohort of subjects.

“Women aren’t studied enough, particularly when it comes to sports-related research,” said Schimmoeller. “Most studies just focus on male athletes.”

“We should have answers to many of these basic physiological questions already,” said Schimmoeller. “But at least, with Cedars-Sinai’s support, we are now uncovering more of the unique attributes of women’s bodies.”