Immunotherapy: The Fourth Pillar of Cancer Care

Date

December 27, 2021

Date

December 27, 2021

Credits

Medical providers featured in this article

In Brief

{{cta-block}}

When people think of treatment for cancer, they often think of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. The three treatment pillars of oncology have saved or prolonged countless lives, and scientists have made great strides in each of these approaches.

Still, cancer remains a profound challenge for modern medicine, an elusive target that requires innovative thinking as researchers search for breakthroughs. For some cancers, one of the biggest breakthroughs has arrived: immunotherapy.

"Immunotherapy has tremendous potential, and this is a truly exciting time in cancer research."

A decade of revolutionary change

It didn't come easy. "The idea of immunotherapy had been around for decades, but it took time to turn the idea into effective treatments," says Dr. Ani S. Balmanoukian, director of Thoracic Oncology at The Angeles Clinic and Research Institute, a Cedars-Sinai affiliate.

The idea was always brilliant: to harness the patient's own immune system to fight cancer cells while leaving healthy cells alone. The first modern immunotherapy didn't come about until 2011, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a groundbreaking treatment against melanoma.

"That was the start of a decade of dramatic progress, as immunotherapy went from experimental to mainstream," says Dr. Johnny K. Chang, a hematologist oncologist and director of Cedars-Sinai Valley Oncology. Immunotherapies are now standard treatment for not only melanoma, but also cancers of the lung, bladder, head and neck, and esophagus, as well as renal cell cancer. They are also used for some cancers of the blood.

In CS Magazines: A Storied Life

What's unique about immunotherapy?

As the name implies, immunotherapy helps your immune system fight cancer, just as it fights infections and other diseases. As part of its natural function, the immune system tries to destroy abnormal cells.

Unfortunately, cancer cells are good at avoiding destruction. Immunotherapy strengthens your body's resources so it can win that battle not just during treatment, but later, in case the cancer comes back.

"One of the things that's revolutionary about immunotherapy is that it keeps working long after you stop the treatment, unlike chemotherapy, which delivers a drug aimed at killing existing, fast-growing cells," explains Dr. Balmanoukian. "Because chemotherapy can't distinguish between healthy and abnormal cells, it's also often accompanied by difficult side effects. Immunotherapy doesn't carry that same kind of risk, and it's usually very well tolerated."

Life-saving results

Immunotherapy can also lead to outcomes that would have been impossible just 10 years ago. "We're seeing patients who had advanced cancers go into prolonged remission," says Dr. Karen L. Reckamp, director of Medical Oncology at Cedars-Sinai.

Dr. Balmanoukian has witnessed extraordinary results in her clinic. "I have a patient who had stage 4 lung cancer. Eight years after treatment with immunotherapy, her cancer has not returned," she says.

Results can vary

Here's the rub: Immunotherapy doesn't work for every cancer or patient, and some combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are still the optimal treatments for many. There is no immunotherapy approved for pancreatic cancer, for example, and no effective version for breast cancer and prostate cancer either.

"But we're making headway all the time," says Dr. Reckamp. "Some therapies are approved across multiple cancers, and we are also using immunotherapy following surgery to improve the potential for cure."

What to expect

Most immunotherapies are delivered via infusion, and treatment often takes place every two, three, four or six weeks depending on your case. Some forms of immunotherapy are given in cycles, with a period of treatment followed by a period of rest to give your body time to recover and mount a response.

Sometimes the best approach combines immunotherapy with other treatments, and at other times it is effective enough on its own. There are as many variations of cancer as there are patients, so it's hard to predict exactly what will work without a thorough evaluation of each individual case.

"It is essential to take time to get to know the patient and really understand their situation," says Dr. Balmanoukian.

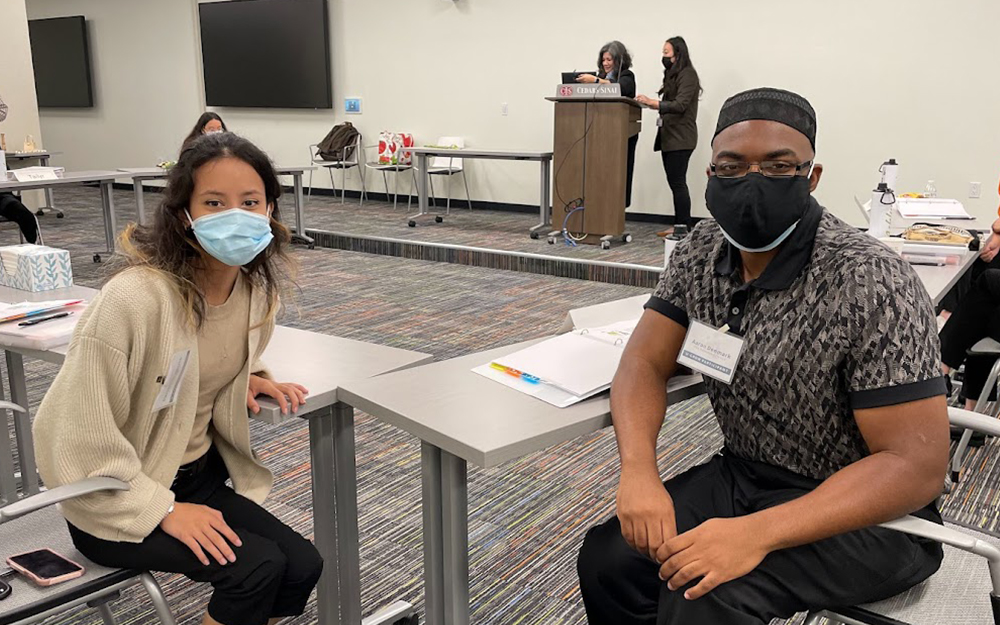

Dr. Chang agrees: "Every case is unique, and the right treatment depends on many factors, not just on the type of cancer the patient has. At Cedars-Sinai, we emphasize personalized medicine, so we create an individualized treatment plan for every patient, and a multidisciplinary team to help ensure the best possible outcome."

Immunotherapy comes in many forms, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, which inhibit the immune system's normal dampeners, allowing it to mount a more powerful response. Another type involves the transfer of immune cells: Cells are taken from your tumor, and those that appear most active against cancer are altered in the lab to make them even better at attacking your cancer cells.

They're grown in large batches and put back into your body.

Monoclonal antibodies (MABs) are also an important type of immunotherapy. MABs are immune system proteins that are made in the lab and designed to bind to specific targets on cancer cells.

Looking ahead

While immunotherapy represents a major advance, it won't work for everyone, even when it's combined with other treatments. The field is still young and there is much that isn't known, including why some patients don't improve while others get dramatically better.

"That's one of the focuses of research. We want to learn how to better predict for whom it will work, and hopefully create more therapies for a wider range of cancers and patients," says Dr. Balmanoukian.

Dr. Reckamp sums up the sentiment among her colleagues: "Immunotherapy has tremendous potential, and this is a truly exciting time in cancer research."